I’ve been researching the potential of consumer trust labels for IoT for quite some time as I believe that trustworthy connected products should be easier to find for consumers, and the companies (or other organizations) that make connected things should have a way to differentiate their products and services through their commitment to privacy, security, and overall just better products.

One milestone in this research was a report I authored last fall, A Trustmark for IoT, based on research within the larger ThingsCon community and in collaboration with Mozilla Foundation. (Full disclosure: My partner works for Mozilla.)

Ever since I’ve been exploring turning this research into action. So far this has taken two strands of action:

- I’ve been active (if less than I wanted, due to personal commitments) in the #iotmark initiative co-founded by long-time friend and frequent collaborator Alexandra Deschamps-Sonsino. The #iotmark follows a certification model around privacy, security, and related topics.

- I’ve also been collecting thoughts and drafting a concept for a separate trustmark that follows a commitment model.

At this point I’d like to share some very early, very much draft stage thoughts about the latter.

A note: This trustmark is most likely to happen and be developed under the ThingsCon umbrella. I’m sharing it here first, today, not to take credit but because it’s so rough around the edges that I don’t want the ThingsCon community to pay for any flaws in the thinking, of which I’m sure there are still plenty. This is a work in progress, and shared openly (and maybe too early) because I believe in sharing thought processes early even if it might make me stupid. It’s ok if I look stupid; it’s not ok if I make anyone else in the ThingsCon community look stupid. That said, if we decide to push ahead and develop this trustmark, we’ll be moving it over to ThingsCon or into some independent arrangement—like most things in this blog post, this remains yet to be seen.

Meet Project Trusted Connected Products (working title!)

In the trustmark research report, I’ve laid out strengths and weaknesses of various approaches to consumer labeling from regulation-based (certification required to be allowed to sell in a certain jurisdiction) to voluntary-but-third-party-audited certification to voluntary-self-audited labels to completely self-authorized labels (“Let’s put a fancy sticker on it!”). It’s a spectrum, and there’s no golden way: What’s best depends on context and goals. Certifications tend to require more effort (time, money, overhead) and in turn tend to be more robust and have more teeth; self-labeling approaches tend to be more lightweight and easier to implement, and in turn tend to have less teeth.

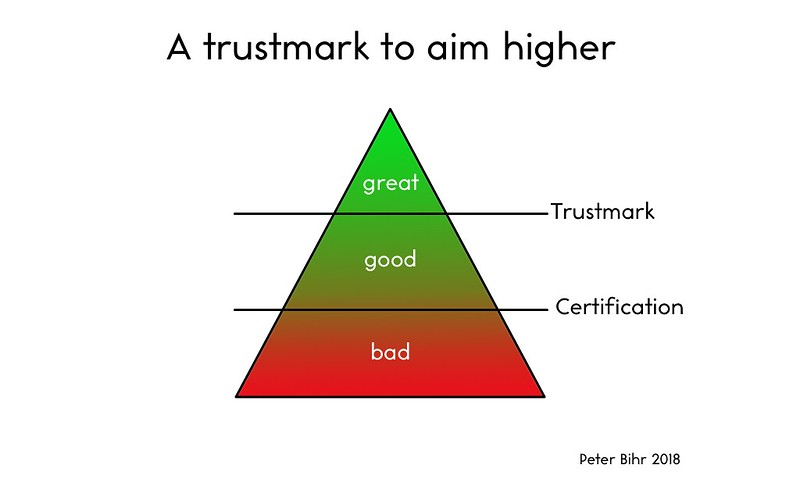

The mental model I’ve been working with is this: Certifications (like the #iotmark) can be incredibly powerful at weeding out the crap, and establishing a new baseline. And that’s very powerful and very important, especially in a field as swamped by crappy, insecure, not-privacy-respecting products like IoT. But I’m not an expert in certifications, and others are, so I’d rather find ways of collaborating rather than focusing on this approach.

What I want to go for instead is the other end of the spectrum: A trustmark that aims not at raising the baseline, but a trustmark that raises the bar at the top end. Like so:

Image: Peter Bihr (Flickr)

Image: Peter Bihr (Flickr)

I’d like to keep this fairly lightweight and easy for companies to apply, but find a model where there are still consequences if they fail to follow through.

The mechanism I’m currently favoring leans on transparency and a control function of the public. Trust but verify.

Companies (or, as always, other orgs) would commit to implementing certain practices, etc., (more on what below) and would publicly document what they do to make sure this works. (This is an approach proposed during the kickoff meeting for the #iotmark initiative in London, before the idea of pursuing certification crystalized.) Imagine it like this:

- A company wants to launch a product and decides to apply for the trustmark. This requires them to follow certain design principles and implement certain safeguards.

- The company fills out a form where they document how they make sure these conditions for the trustmark are met for their product. (In a perfect world, this would be open source code and the like, in reality this wouldn’t ever work because of intellectual property; so it would be a more abstract description of work processes and measures taken.)

- This documentation is publicly available in a database online so as to be searchable by the public: consumers, consumer advocates and media.

If it all checks out, the company gets to use the label for this specific product (for a time; maybe 1-2 years). If it turns out they cheated or changed course: Let the public shaming begin.

This isn’t a fool proof, super robust system. But I believe the mix of easy-to-implement-but-transparent can be quite powerful.

What’s in a trustmark?

What are the categories or dimensions that the trustmark speaks to? I’m still drafting these and this will take some honing, but I’m thinking of five dimensions (again, this is a draft):

- Privacy & Data Practices

- Transparency

- Security

- Openness

- Sustainability

Why these five? IoT (connected products) are tricky in that they tend not to be stand-alone products like a toaster oven of yore.

Instead, they are part of (more-or-less) complex systems that include the device hardware (what we used to call the product) with its sensors and actuators and the software layer both on the device and the server infrastructure on the backend. But even if these were “secure” or “privacy-conscious” (whatever this might mean specifically) it wouldn’t be enough: The organization (or often organizations, plural) that make, design, sell, and run these connected products and services also need to be up to the same standards.

So we have to consider other aspects like privacy policies, design principles, business models, service guarantees, and more. Otherwise the ever-so-securely captured data might be sold or shared with third parties, it might be sold along with the company’s other assets in case of an acquisition or bankruptcy, or the product might simply cease working in case the company goes belly-up or changes their business model.

This is where things can get murky, so we need to define pretty clear standards of what and how to document compliance, and come up with checklists, etc.

In some of these areas, the ThingsCon community has leading experts, and we should be able to find good indicators ourselves; in others, we might want to find other indicators of compliance, like through existing third party certifications, etc.; in others yet, we might need to get a little creative.

For example, a indicator that counts towards the PRIVACY & DATA PRACTICES dimension could be strong (if possibly redundant) aspects like “is it GDPR compliant”, “is it built following the Privacy by Design principle”, or “are there physical off-switches or blockers for cameras”. If all three checkboxes are ticked, this would be 3 points on the PRIVACY & DATA PRACTICES score. (Note that “Privacy by Design” is already a pre-condition to be GDPR compatible; so in this case, one thing would add two points; I wouldn’t consider this too big an issue: After all we want to raise the bar.)

What’s next?

There are tons of details, and some very foundational things yet to consider and work out. There are white spots on the metaphorical map to be explored. The trustmark needs a name, too.

I’ll be looking to get this into some kind of shape, start gathering feedback, and also will be looking for partners to help make this a reality.

So I’m very much looking forward to hear what you think—I just ask to tread gently at this point rather than stomping all over it just yet. There’ll be plenty of time for that later.