Attack of the VR headsets! Admittedly, this photo has little to do with the topic of this blog post. But I liked it, so there you go.

The internet, it seems, has turned against us. Once a utopian vision of free and plentiful information and knowledge for all to read. Of human connection. Instead, it has turned into a beast that reads us. Instead of human connection, all too often we are force-connected to things.

This began in the purely digital realm. It’s long since started to expand into the physical world, through all types of connected products and services who track us—notionally—for our own good. Our convenience. Our personalized service. On a bad day I’m tempted to say we’ve all allowed to be turned into things as part of the the internet of things.

///

I was born in 1980. Just on the line that marks the outer limit of millenial. Am I part of that demographic? I can’t tell. It doesn’t matter. What matters is this:

Those of us born around that time might be the last generation that grew up who experienced privacy as a default.

///

When I grew up there was no reason to expect surveillance. Instead there was plenty of personal space: Near-total privacy, except for neighbors looking out of their windows. Also, the other side of that coin, near total boredom—certainly disconnection.

(Edit: This reflects growing up in the West, specifically in Germany, in the early 1980s—it’s not a shared universal experience, as Peter Rukavina rightfully points out in the comments. Thanks Peter!)

All of this within reason: It was a small town, the time was pre-internet, or at least pre-internet access for us. Nothing momentous had happened in that small town in decades if not centuries. There it was possible to have a reasonably good childhood: Healthy and reasonably wealthy, certainly by global standards. What in hindsight feels like endless summers. Nostalgia past, of course. It could be quite boring. Most of my friends lived a few towns away. The local library was tiny. The movie theater was a general-purpose event location that showed two movies per week, on Monday evenings. First one for children, than one for teenagers and adults. The old man who ticketed us also made popcorn, sometimes. I’m sure he also ran the projector.

Access to new information was slow, dripping. A magazine here and there. A copied VHS or audio tape. A CD purchased during next week’s trip to the city, if there was time to browse the shelves. The internet was becoming a thing, I kept reading about it. But until 1997, access was impossible for me. Somehow we didn’t get the dialup to work just right.

What worked was dialing into two local BBS systems. You could chat with one other person on one, with three in the other. FIDO net made it possible to have some discussions online, albeit ever so slowly.

///

When I grew up there was no expectation of surveillance. Ads weren’t targeted. They weren’t even online, but on TV and newspapers. They were there for you to read, every so often. Both were boring. But neither TVs nor newspapers tried to read you back.

///

A few years ago I visited Milford Sound. It’s a fjord on the southern end of New Zealand. It’s spectacular. It’s gorgeous. It rains almost year round.

If I remember a little info display at Milford Sound correctly, the man who first started settling there was a true loner. He didn’t mind living there by himself for decades. Nor, it seems, when the woman who was to become his wife joined. It’s not entirely clear how he liked that visitors started showing up.

Today it’s a grade A tourist destination, if not exactly for mass tourism. It looks and feels like the end of the world. In some ways, it is.

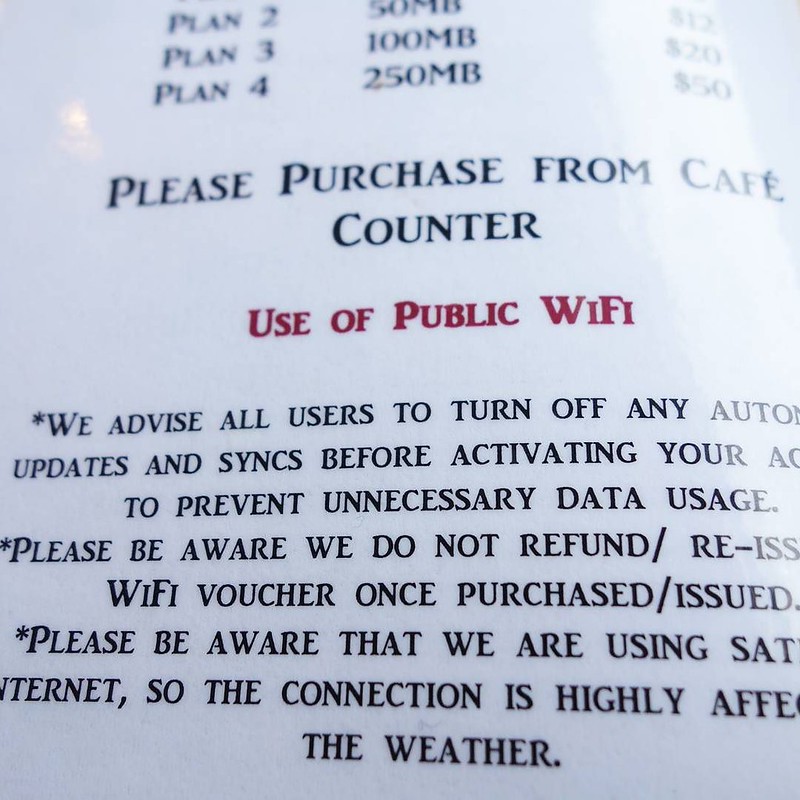

As we sought shelter from the pouring rain in the boat terminal’s cafeteria, our phones had no signal. Even there, though, you could connect to the internet.

Connectivity in Milford Sound comes at a steep price

Internet access in Milford Sound is expensive enough that it might just suffice to stay offline for a bit. It worked for us. But even there, though they might be disconnected, the temps who work there during tourist season probably don’t get real privacy. On a work & travel visa, you’re likely to live in a dorm situation.

///

The internet has started to track every move we make online. I’m not even talking about governance or criminal surveillance. Called ad tech, online advertisements that track your every move notice more about you than you about them. These are commercial trackers. On speed. They aren’t restricted to one website, either. If you’ve ever searched for a product online you’ll have noticed that it keeps following you around. Even the best ad blockers don’t guarantee protection.

Some companies have been called out because they use cookies that track your behavior that can’t be deleted. That’s right, they track you even if you explicitly try to delete them. Have you given your consent? Legally, probably—it’s certainly hidden somewhere in your mobile ISP’s terms of service. But really, of course you haven’t agreed. Nobody in their right mind would.

///

Today we’re on the brink of taking this to the the next level with connected devices. It started with smartphones. Depending on your mobile ISP, your phone might report back your location and they might sell your movement data to paying clients right now. Anonymized? Probably, a little. But these protections never really work.

Let’s not but let’s be very deliberate about our next steps. The internet has brought tremendous good first, and then opened the door to tracking and surveillance abuse. IoT might go straight for the jugular without the benefits – if we make it so. If we allow to let that happen.

///

The internet, it seems, has turned against us. But maybe it’s not too late just yet. Maybe we can turn the internet around, especially the internet of things. And make it work for all of us again. The key is to reign in tracking and surveillance. Let’s start with ad tech.

1 Comment

J.P. Rangaswami spoke about privacy at the reboot conference in 2006 in Copenhagen; although the transcript of video of his talk are lost to time, he touched on some of the same issues in a 2010 blog post (http://confusedofcalcutta.com/2010/08/19/thinking-about-privacy-and-asymmetry/), where he started:

“As many of you know, I was born there. A teeming city with many millions of people. I spent much of my childhood and youth in a small flat with an open-door guest policy; it was rare that we had less than 10 people staying in what was essentially a 2-bed 1500 square foot perch. I was educated at St Xavier’s Collegiate School (and College) from 1966 to 1979; I think we had around 1200 students in the school, and over twice that number at the college.

So I was used to crowds, and to living in vertical stacks. My concepts of privacy were therefore somewhat different from those that would have been obtained by people brought up in many parts of the West.”

J.P. made me realize that your suggestion that “Those of us born around that time might be the last generation that grew up who experienced privacy as a default.”–a notion that I share–is a notion rooted in our experience, and one that is not universal.

One way of understanding more about the disappearance of privacy is to talk with people who’ve never had it, and to consider whether our obsession with privacy is a recent construction that might not be as relevant as we think. It was in search of some of those ideas that I set out to develop a lecture I delivered to a Philosophy of Technology course in 2009 called “Privacy and the Obligation to Explain” (https://speakerdeck.com/reinvented/privacy-and-the-obligation-to-explain), for which I owe J.P. a great debt.